What isAnxiety?

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines anxiety as “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes like increased blood pressure.”

It is important to understand the difference between normally occurring anxiety and a diagnosable anxiety disorder that is disruptive to daily life and requires professional intervention. Everyone experiences anxiety at times throughout their life. To be clear, some anxiety is a normal and biologically helpful response to certain types of stress. Anxiety is not always a bad thing; besides providing what can sometimes be a constructive motivating force (for example, worry about providing for a family motivates a head of household to work hard and get a promotion), it can also keep us and our loved ones safe from danger.

“Anxiety…can keep us and our loved ones

safe from danger.”

So-called “anxiety distress,” or uneasiness of mind caused by fear of danger or misfortune, is also a natural response to many of life’s events. Healthy anxiety distress is related to a specific situation. For example, while awaiting the results of a serious medical test it is common to feel some anxiety, because the results could indicate a life-threatening condition. During this time, common signs of anxiety like trouble sleeping or concentrating on work would be a completely expected response. Because it is tied to specific situations, normal anxiety distress will also dissipate when the causative crisis has resolved itself. This means that if the medical test came back fine, a healthy person would quickly return to their baseline level of functionality.

Whenever we are startled or frightened, our brains also respond with anxiety and physiological changes that make us prepared to start a “fight or flight” response. When we are frightened, our bodies release excess cortisol and other hormones into our bloodstream. This process increases heart rate and respiration, increases blood glucose levels, and sharpens sensory perception. This ancient pathway in our bodies once protected our ancestors from existential dangers like predators. Although most modern humans do not have to worry about bears on a daily basis, the powerful “fight or flight” system built into each of us remains virtually unchanged from our time living in the forest. Unfortunately, what was once a very necessary and useful response to danger can pose some serious problems if it gets triggered too often by non-life threatening events. There is increasing evidence that chronic stimulation of our “fight or flight” system leads to a litany of health conditions including insulin resistance, susceptibility to infections and cancer, depression, and an increased risk of stroke.

“While passing anxieties are entirely normal,

too much anxiety can have serious physical

and psychological effects.”

Essentially, one of the biggest problems with anxiety is that we are naturally wired to respond strongly to stimuli; it’s literally in our DNA. We also know that while passing anxieties are entirely normal, too much anxiety can have serious physical and psychological effects. So when, exactly, does someone’s level of anxiety start to be a problem?

To begin with, “normal” anxiety is transitory, generally in response to a specific situation, and goes away quickly. The APA describes a patient as having an anxiety disorder when they are “having recurring intrusive thoughts or concerns” and the level of anxiety they are experiencing is out of proportion with the reality of their surroundings. For example, if someone almost gets into a car wreck on the way to work, it would be entirely normal for them to experience a moment of fear and anxiety, including physical symptoms such as nausea, increased heart rate, or excessive sweating. What is abnormal, however, would be continuing to fixate on the possibility of a car accident for the rest of the day or even lose sleep over it that night. Persons with an anxiety disorder are constantly in fear, to the point where daily life is being disrupted by physical and emotional symptoms. These symptoms can cause people to miss work or school, have trouble sleeping, and even ruin relationships, all without a clearly definable stressor of a magnitude equal to their response.

“Anxiety disorders were only officially

recognized by the American Psychiatric

Association in 1980.”

What we now refer to as anxiety disorders (panic attacks, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety, etc.) have probably always been part of the human experience. In earlier periods of medical history, people experiencing the more severe end of the anxiety spectrum were frequently blamed for their own condition, abandoned to asylums, or were attempted to be cured with quack remedies. These “therapies” included religious rituals, hydropathy, harmful herbal preparations or addictive substances like the opium given to soldiers returning from war, and even ECT (electroshock) therapy. Women in particular suffered being labeled as “hysterical” as far back as ancient Greece, where the term was coined by physicians who blamed their female anatomy for psychiatric or behavioral problems. Indeed, anxiety disorders were only officially recognized by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980. Prior to that, there was little formal discussion or training for medical and psychiatric professionals regarding effective treatments for anxiety.

One of the first official anxiety-related clinical conversations revolved around what we now know as PTSD but which used to be called “shellshock” during WW I and II or “soldier’s heart” after the Civil war. It was first called “soldier’s heart” because cardiologists noted that soldiers were returning from combat in the 1860s conflict with elevated heart rates along with altered consciousness, flashbacks, and trouble sleeping. “Shellshock” was a later theory that the physical impact of shells and other projectiles was somehow having a physical effect on the brain that resulted in what we now know to be classic PTSD symptoms. While there was acknowledgement that these conditions were affecting soldiers, it took decades longer (and the Vietnam war) for psychologists and psychiatrists to start seriously studying PTSD and pioneering treatments for what can be a difficult and complex syndrome to diagnose and treat.

With the rise of Freudian psychoanalysis during the early part of the 20th century, there was finally some clinical training for providers to help patients suffering from other types of anxieties, particularly excessive fixations and phobias–but most of the early psychoanalysts were working from theoretical frameworks that weren’t necessarily evidence-based, leading to limited benefit for patients. One of the first truly effective treatments for phobias or specific fears was exposure therapy, which was first developed in the 1950s. During this type of exposure therapy, the patient is systematically exposed to the trigger of their fear with the goal of desensitizing them and lessening their anxiety or phobia. This method is still in use today to treat some types of phobias.

Also during the 1950s, psychotropic prescription medication began to gain popularity as a way to treat anxiety and sleeplessness. Early medications like barbiturates were very effective at treating the short-term symptoms of anxiety, but ultimately also proved themselves to be addictive. Also popular is a dangerous group of medications called benzodiazepines.

Although these medications are generally considered safer, they can still be habit-forming and risky, especially if mixed with alcohol. In the 1990’s, newer types of antidepressant medication called SSRIs and SNRIs were developed that were more useful than earlier generations of drugs with less severe side effects. Researchers discovered areas of overlap in the brain between the chemical processes that govern symptoms of anxiety and depression. Soon, psychiatrists found success treating some anxiety disorders with these medications, which are much safer for long-term use than benzodiazepines.

Today, anxiety has been fairly well-studied and accepted as a legitimate diagnosis by most of the world’s mental health practitioners. Therapy is the preferred “first line” treatment, and sometimes medication is also prescribed if symptoms are severe enough.

Anxiety: The most common

form of mental illness in the

United States

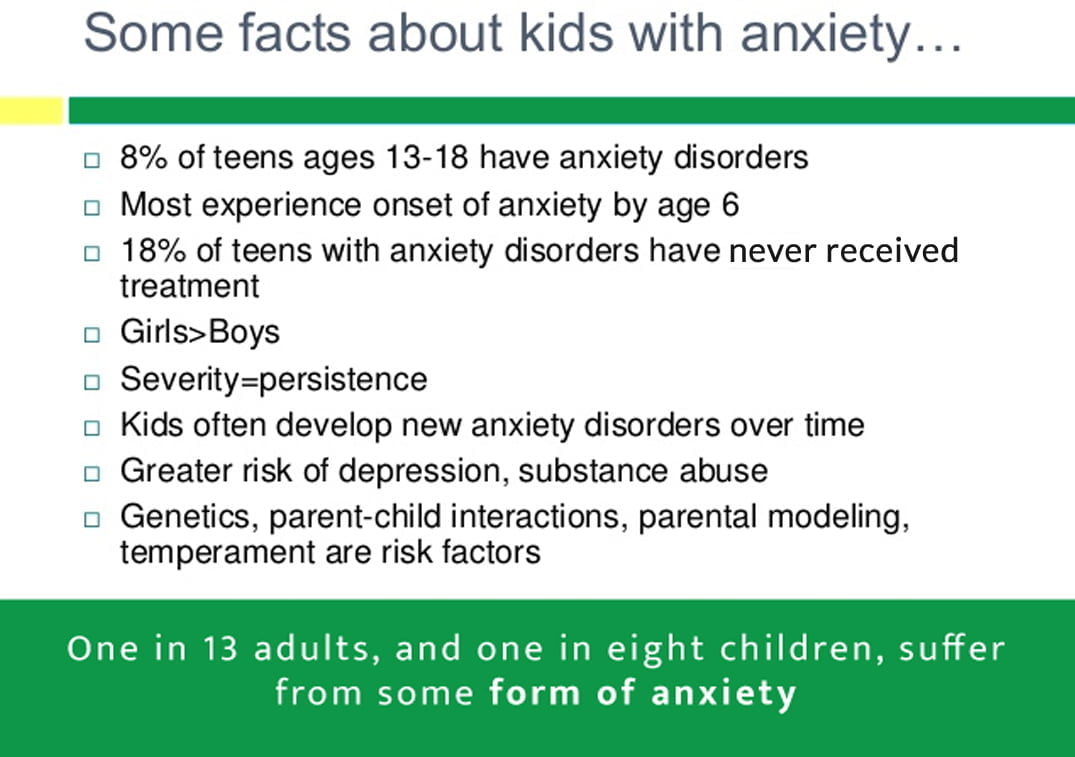

According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA), over 40 million Americans over the age of 18 suffer from some form of an anxiety disorder. Of those, 7 million suffer from Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and 15 million suffer from Social Anxiety Disorder. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) affects approximately 7.7 million Americans. Altogether, the number of people who meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder make up almost 20% of the adult population. The problem is not just confined to America, either: globally, it is estimated that some 1 in 13 adults suffer from some form of anxiety, making it one of the most common diagnosable disorders on the planet.

“One in 13 adults, and one in eight children,

suffer from some form of anxiety.”

A great many children and adolescents also suffer from various forms of anxiety disorders. Currently, it is estimated that one in eight children in the United States suffer from an anxiety disorder or PTSD. When it comes to brain development, scientists are just beginning to understand how disruptive chronic exposure to cortisol and adrenaline (the “anxiety hormones”) are; for children that experience trauma or otherwise have a heightened anxiety response, there can be permanent changes to the frontal cortex and areas that control emotional regulation and access to memory. This makes it especially important that treatment be made available to children and adolescents who are struggling with PTSD, social anxiety, or GAD. Proven therapies like the cognitive-behavioral model can help children of every age learn to manage and lessen symptoms, which will in turn provide some protection against the extremely damaging neuropsychiatric effects of high amounts of stress hormones on the developing brain.

Because they are so common, the burden of anxiety disorders is also massive. Besides sizable economic and productivity impacts, the sheer number of cases means that statistically speaking, most Americans are close with someone who struggles with untreated anxiety. Associated behaviors can be disruptive to families and communities in the form of addiction, unhealthy relationships, poor work ethic, and other maladaptive coping skills.

Because they are so common, the burden of anxiety disorders is also massive. Besides sizable economic and productivity impacts, the sheer number of cases means that statistically speaking, most Americans are close with someone who struggles with untreated anxiety. Associated behaviors can be disruptive to families and communities in the form of addiction, unhealthy relationships, poor work ethic, and other maladaptive coping skills.

How do I know if I have an Anxiety Disorder?

Life is stressful, and when that stress is prolonged it can take a toll on productivity, relationships, and even physical health. While none of us can expect to go through life without some worry, anxiety essentially becomes a diagnosable condition when it starts to create a pattern of interference in regards to normal life activities like self-care, relationships, and work or study. This interference can come directly from physical symptoms of anxiety, or indirectly through the secondary effects of not being able to sleep or concentrate.

Without a doubt, severe anxiety can cause serious and measurable physical symptoms. We have all heard the warnings about chest pains and shortness of breath–these are some of the common first signs of a heart attack, after all. Every single day, people with untreated severe anxiety show up in emergency rooms with frightening symptoms that nonetheless test negative for a heart attack. Frustrated patients may not feel staff are taking them seriously enough, while emergency room doctors may find themselves at a loss to explain serious chest pain when the EKG comes back fine.

Needless to say, if you find yourself incapacitated to the point where you have to get checked out by a medical professional, it may be time to consider seeking the treatment of a professional for anxiety. Although in the short term, a panic attack is certainly less deadly than a heart attack, the long-term consequences of our “fight or flight” hormones coursing through the body can be profoundly damaging. At the same time, trying to live with such intrusive symptoms is so time- and energy-intensive that it can result in significant problems with our overall ability to function in normal life. Although one may suspect an anxiety disorder, the only way to know for sure is to be evaluated by a licensed provider of mental health services.They can also help distinguish between anxiety attacks and panic attacks.

Besides leading to severe physical symptoms, anxiety can sneak up on even the most stalwart individual because our “fight or flight” response evolved by nature to be triggered very easily. Modern-day stimuli like email or text messaging notifications can signal the same portion of the cerebral cortex that originally dealt with reacting to rattlesnakes, except instead of being occasional (in the case of our ancestors), it’s constant (in the case of our workday). This is part of what accounts for the outsize response that modern life can have on our anxieties. The problem is that our bodies don’t know the difference, and we end up suffering from the toxic effects of too much cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine, leading to symptoms that can be more subtle than a full-blown panic attack while still being quite bad for us both physically and psychologically. Anxiety also often impacts women and men differently.

Essentially, this means that anxiety disorders can be incredibly easy to develop, which probably accounts for why they are so common. The key in understanding the problem is whether or not either the symptoms or secondary problems related to the symptoms are having a noticeable impact on quality of life.

Take a fear of driving, for example. It’s not totally unjustified–driving certainly can be dangerous. Although deaths are fairly rare, most of us hear of fatal car accidents on the news, and see these images frequently. A normal response to this fear is to take certain precautions, like wearing seat belts, making sure children are in appropriate car seats, obeying traffic laws, etc. With an understanding of the risk, and having taken precautions, most people still feel OK using a vehicle to get where they need to go.

For someone with a fear of driving that could meet the diagnostic criteria of an anxiety disorder, however, things are not so simple. This individual may be so focused on all the potential danger involved in getting behind the wheel that it takes tremendous mental and emotional struggle just to sit down behind the wheel. Intrusive thoughts about how likely an accident is can even make anxious people change their habits, such as avoiding highways or driving at night. In extreme instances, someone with severe untreated anxiety may become so fearful that they stop driving altogether and even refuse to ride as a passenger. This level of fear can lead to problems getting or staying employed, keeping relationships intact, and even providing for basic needs.

Excessive worry and fixation around social situations are also common symptoms of an anxiety disorder. These symptoms happen when the mind will not shut off after an appropriate amount of time trying to work out a problem, conversation, or other interaction. Instead of getting resolved, the scenario gets stuck in a loop that continues to repeat with the same high level of emotional intensity. Again, this crosses into the level of something that needs treatment if the second-guessing is becoming intrusive, leading to loss of sleep, preventing decision-making, or interfering with your ability to have normal social interaction.

“Excessive worry and fixation around social

situations are also common symptoms of an

anxiety disorder.”

Fortunately, because anxiety has become a more high-visibility condition, there is now plenty of help available. There are several evidence-based techniques, like cognitive-behavioral therapy, that have been proven in multiple studies to have a positive impact on many mental health diagnoses, including anxiety. If you’re genuinely struggling with anxiety and think it may be time for outside help, simply checking in with a therapist is a great place to start because it can provide perspective about whether or not further treatment may be useful. For both your own protection and to increase the chances that your insurance will cover the treatment, always look for a licensed therapist with a reputable practice.

Going in to seek evaluation for anxiety is straightforward and no need for further worry! Typically, providers will start an introductory session by taking a brief life history including any relevant medications or past treatment, and will then discuss any goals you have (for instance, being able to drive on the highway or give a presentation for work) along with types of therapy that may be appropriate and time lines for treatment.

Different Type of Anxiety Disorders

Although anxiety may manifest differently depending on the personality type, cultural background, age, and gender of the client, anxiety disorders do fall into several distinct categories. Some of the most common are Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Social Anxiety, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Panic Disorder, phobias, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). While self-diagnosis may be tempting, it is better for anyone curious about whether they suffer from an anxiety disorder to seek out the opinion of a professional.

The severity of life impairment suffered by some people with these diagnosis is a great reminder that these are real, diagnosable conditions and joking that someone is “OCD” or making other off-handed comments about disorders that most people have heard of is unhelpful and furthers harmful stigmas that may actually be preventing people from seeking help.

While the general public may refer to various different types of anxiety, a mental health professional will use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM V) to determine if an individual meets the clinical diagnostic criteria for a disorder. Below are details about some of the more commonly diagnosed anxiety and panic disorders.

General Anxiety Disorder (GAD), is the diagnosis given when someone presents with signs and symptoms of an anxiety disorder, but it does not clearly fall into one of the more specific categories named above. For example, an individual suffering from GAD may experience a mixture of symptoms from both Social Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. The primary underlying commonality is that anxiety is present in some form and it is disruptive enough to be interfering with the client’s life in an important area like work, life, or relationships.

Many people who suffer from GAD have found relief through cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT. This type of therapy focuses on identifying the negative thoughts that lead to anxiety and learning new positive ways to direct those thoughts. It focuses on changing thoughts and behaviors to help the individual experience less anxiety and more contentment in their daily life. Because CBT can be used to both prevent thought processes that worsen anxiety and alleviate the anxiety when it does appear, it’s a tremendously useful tool for anyone with GAD who is trying to improve their quality of life.

Social anxiety is somewhat misunderstood in popular culture– it’s much more than just shyness. While most people fall somewhere along the category of “extrovert” or “introvert”, social anxiety by definition falls outside of the spectrum of a normal introvert or “shy” person. Instead, social anxiety is one of several anxiety disorders that is characterized by an intense fear of social interactions, often including intrusive thoughts about being judged or watched. Social anxiety causes the sufferer to fear social settings, public spaces, and meeting new people. Some people with severe social anxiety may feel quite uncomfortable even around people already known to them. True social anxiety can interfere significantly with daily life, often making work, school, and family relationships, friendships, and romantic relationships very difficult.

“Some people with severe social

anxiety may feel quite

uncomfortable even around people

already known to them.”

There are multiple theories about what causes social anxiety, but it probably is a combination of genetics (nature) and upbringing (nurture), and it exists on a spectrum. Again, although many people may be afraid of public speaking at work, a diagnosis of social anxiety may be merited if the symptoms are causing significant impairment– for example, someone can’t even speak up to the small team they’ve been collaborating on a project with for a year.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be one of the most well-known of all the anxiety disorders, although it is not the most commonly-occurring. It is most commonly associated with military combat veterans. While this portion of our society is at a high risk for developing PTSD, they are certainly not alone. In fact, anyone that endures a traumatic event can develop this disorder. People who have experienced natural disasters, epidemics, or terrorist attacks are all at risk for this disorder. Some other common events that can lead to PTSD are being a victim of a serious crime such as rape, assault, car accident, or stalking. For some people, even witnessing a violent crime or accident can trigger PTSD symptoms.

“People with PTSD have a high likelihood of

suffering from co-morbid disorders like

substance abuse or depression.”

When exposed to a significant trauma, our brains are kicked into an automatic response for dealing with the situation – fight, flight or freeze – and the situation leaves a powerful imprint on the memory. In the past, this may have helped our ancestors learn to avoid danger, but the strong imprint of the memory can lead to a litany of negative side effects ranging from flashbacks, changes in habits, hypervigilance, and nightmares or insomnia. Essentially, someone suffering from PTSD is often mentally living as if that tragic event is still happening.

The sheer power of our body’s “fight or flight” response can short-circuit normal coping skills, including using higher brain functions like logic to remind the sufferer that they are actually out of danger. For this reason, PTSD is associated with a higher likelihood of negative impact to quality of life. For example, people with PTSD have a high likelihood of suffering from co-morbid disorders like substance abuse or depression, and should be treated by a professional as soon as possible.

Panic disorder causes persons suffering from it to experience severe panic or anxiety attacks when faced with certain common triggers. These triggers can be anything that cause a feeling of fear in the individual; the difference is just that the response is outsized compared to a “normal” person. In people suffering from panic disorder, the body’s fight or flight instinct is more easily triggered, leading to a powerful response in normal or inappropriate situations. For example, people with panic disorder may have serious trouble with flying, crowds, driving, elevators, and other every-day situations.

An anxiety attack, or panic attack, is an intense physical sensation that becomes a problem once it begins to severely limit a person from continuing with the immediate task at hand. This feeling can include a racing heart rate, sweating, shaking, trembling, nausea and vomiting, difficulty breathing, and lightheadedness. These feelings, while intense, usually dissipate fairly quickly. A pattern of panic attacks is a key part of panic disorder, and it is this pattern that leads to the diagnosis; again, it becomes a problem once quality of life starts being affected. For people with panic disorder, the worry of experiencing a debilitating attack may lead him or her to avoid settings where they are likely to occur, thus further limiting their ability to function in normal daily life.

Phobias are visceral, specific fears that can sometimes become disruptive or debilitating. Phobias can range from a mild aversion to extreme, debilitating fear. Phobias are often rooted in a negative experience that happened at a formative time in their brain’s development. Regular fear becomes a phobia when the response elicited by the subject grows out of proportion to the perceived threat.

Interestingly, there is some scientific evidence that certain phobias may be “hard-wired” into our brains, often in the form of avoidance to certain dangers that may have helped our ancestors survive. While a fear of heights is fairly self-explanatory, other hard-wired or inherited phobias with less clear origins also exist. An example of this is Trypophobia, or a strong aversion to clusters of holes like those found in a lotus seed pod. One study found that almost 20% of participants shared an intense, visceral reaction when shown images of clusters of holes. Scientists posit that this particular phobia may have been “wired” as an aversion to a visual stimuli that may indicate decay or disease, something that could have helped our ancestors stay safe.

Regardless of where the phobia comes from, experiencing strong fear of potentially dangerous things like spiders and snakes is incredibly common; even Trypophobia affects nearly 1 in 5 people. As with the other anxiety disorders, someone may be a candidate for diagnosis and treatment only if the phobia(s) are causing significant interference with daily activities.

Like other anxiety disorders, phobias can be treated effectively by mental health care professionals. In fact, someone trying to overcome a phobia can seek treatment from someone with a specialization in the field, something that may be easier to do for those open to e-therapy/telemedicine. Phobias can be addressed with CBT or other traditional forms of therapy; specialists in the field sometimes use exposure therapy.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is another very serious clinical diagnosis that often gets misconstrued by popular media. OCD is characterized by intense, intrusive patterns of fearful thought that causes an urge to behave in a certain way, often in the form of “ritual”-like repetitions like tapping, arranging objects, or washing hands and/or surfaces. The fears driving these obsessions stem often from an incorrect belief that repeating this behavior will protect the individual and/or their loved ones from bad luck or danger. While everyone may have occasional bouts of needing things to be arranged a certain way, or being worried about germs, genuine OCD is different. Sufferers who meet the diagnostic criteria for OCD may find themselves so overwhelmed by the urge to repeat their particular compulsive behavior that regular life can become impossible to continue–this is the point when a diagnosis is usually made. Interestingly, unlike many other anxiety disorders, OCD often first appears in childhood. If recognized and treated quickly, it can sometimes resolve itself by adulthood.

There are several subsets of OCD that have also received gratuitous attention in the media recently, such as hoarding. Someone who is hoarding objects or animals in their house to the point where physical health and safety are at risk is better understood as a person who needs help, rather than an interesting subject for a reality TV show. This unfortunate spotlight has done nothing to help the shame and stigma that many hoarders are already suffering from. For most people engaging in this type of behavior, their attachment to objects is a form of compulsion that is often the result of trauma or another co-occurring psychiatric disorder. For these individuals, simply cleaning out the house will not address the root of the problem, and their behavior will not change without help from an experienced mental health professional.

Fortunately, like the other anxiety disorders, the symptoms of OCD (including hoarding) can be managed. There are several kinds of therapy that can be helpful, such as CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) or sometimes DBT (dialectical behavioral therapy). Both of these therapeutic models help people learn to reframe perceptions, manage emotions, learn how to tolerate distress, and cope with the intrusive thoughts in a more constructive manner. Along with therapy, some people with OCD may also be good candidates for medication.

“OCD is characterized by intense, intrusive

patterns of fearful thought that causes an

urge to behave in a certain way.”

Lesser known types of anxiety which are referenced in the DSM-V include: acute stress disorder; adjustment disorder with anxious features; and substance induced anxiety disorder.

Political anxiety is often mentioned in the media and sometimes referred to as post-election stress disorder. Although it is not included in the DSM-V as an official anxiety diagnosis it an issue for man people. The American Psychological Association has reported that nearly two-thirds of people are stressed out about the future of their country. When people feel uncertainty surrounding the political environment it is not uncommon for them to experience anxiety, depression, and sadness.

What Causes Anxiety Disorders?

Like all psychiatric disorders, the causes and diagnosis of anxiety disorders are extremely complex, and anxiety in particular presents unique challenges. To begin with, anxiety disorders exist alongside a powerful, ancient, and very real physiological connection known as the “fight or flight” response that involves a measurable cascade of hormones that can cause serious physical problems with chronic exposure in high amounts. Like other disorders, anxiety is understood to exist on a spectrum. Unlike other common psychiatric diagnoses, however, anxiety can manifest itself in a comparatively large variety of ways, from compulsive behavior, to “freezing”, to panic attacks that can be serious enough to lead to hospitalizations. Because of its connection to biologically important fear and danger-avoidance systems in our brains, everyone is likely to experience some measure of anxiety on a regular basis; the problem starts when anxiety begins to interfere with normal parts of life like work, self-care, school, or relationships.

Fortunately, our scientific understanding of anxiety has increased markedly in the last 20 years, alongside an increase in the quality of brain imaging tools available and the flourishing number of studies that have been published. Currently, anxiety disorders are generally understood to be caused by a complex set of individual circumstances that include both genetic and environmental factors. Unlike other psychiatric disorders like depression, anxiety disorders are also understood to exist in the context of some very ancient parts of our brain. While this means that everyone will experience some anxiety on occasion, why do some people have full-blown panic attacks? Research indicates that there is a strong genetic component that may contribute to anxiety disorders.

While scientists have not isolated a specific gene that makes a person predisposed to an anxiety disorder, a larger cascade of genetic information almost certainly plays a role, as there are measurable neurological differences in people with high levels of anxiety. This means that a risk for higher anxiety is likely a heritable condition. Multi-generational studies including with twins and adopted children have also found that those with a family member who has an anxiety disorder are more likely to also be at risk of developing one, purely from a biological point of view.

Of course, the cause of anxiety isn’t as cut-and-dry as simply being a matter of biology. As we grow and our brains develop, there is a complex interplay between “nature” (our inherited genes) and “nurture” (our lived experiences). To further complicate things, we now know that certain experiences can actually trigger genetic changes that lead to structural differences in the brain. For example, children who experience chronic high levels of cortisol (part of the “fight or flight” response) can actually be at risk of developmental changes in how the frontal cortex processes information, which can affect everything from behavior to normal emotional development. This means that children who grow up experiencing or witnessing abuse, neglect, or other traumatic events are much more likely to experience anxiety (and other disorders) themselves.

There is also a “learned” component to anxiety, where children normalize behavior that can be pathological–such as thinking that the obsessive worrying and panic attacks frequently experienced by a parent are normal. Just like with abuse or neglect themselves, if a child who witnessed a parent with debilitating anxiety replicates this behavior in adulthood with their own children, a generational pattern is created that can be very difficult to disrupt. The other important element of “learned” anxiety is related to a specific event and often comes in the form of PTSD–something that can happen at any age, even to a fully-developed brain.

“Receiving appropriate counseling as

soon as possible after negative

experiences can help prevent a

severe disorder from developing.”

Interestingly, while having a difficult childhood or experiencing severe trauma may place a person at risk for developing one or more anxiety disorders, it does not guarantee that they will. Besides possibly lacking certain genes that make anxiety more likely, some individuals are simply able to process negative events while maintaining a positive outlook on life. Besides possible cultural and behavioral differences that can have a protective effect on the likelihood of developing severe anxiety, early intervention is also tremendously useful. Essentially, receiving appropriate counseling as soon as possible after negative experiences can help prevent a severe disorder from developing.

While anxiety disorders seem to be fairly common in the human brain, the good news is that we have also developed numerous ways to manage the condition. While anxiety or other psychiatric disorders may never be fully “cured”, it is certainly possible to lessen the symptoms to a point where quality of life is no longer being affected. Licensed professionals can employ several methods, like CBT, that have been scientifically proven to improve anxiety scores for people with various diagnoses and backgrounds. While medication is sometimes used in conjunction with treatment, many psychiatrists are moving away from prescribing addictive anti-anxiety medication in favor therapy alone, antidepressants, or other alternatives. For example, there is growing scientific interest in investigating and quantifying the possibly significant beneficial effects of a comparatively simple cure: exercise.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3684250/

Where Do I Go For Help?

If you think you or a loved one is suffering from an anxiety disorder, it is important to seek professional help. There are many options out there, and with a little bit of research you should be able to find the right fit.

Often the first step people take on their road to recovering from an anxiety disorder is getting an official diagnosis. Having a diagnosis is helpful because it can lead you to the most effective type of treatment for your particular type of disorder while also helping to clarify specific treatment goals. Having a diagnosis can also be helpful when dealing with insurance, or when seeking institutional support like developing a school IEP (individual education plan) for a child with the disorder.

Most licensed professionals will begin the diagnostic process with a short medical and life history, followed by a series of diagnostic questions. Depending on the mental health professional, these questions may be completed in the office or at home in preparation of the appointment. Depending on the situation, your counselor may suggest you see a medical doctor to rule out any additional physical illnesses that could be causing your symptoms.

If severe anxiety symptoms are causing someone to become a danger to themselves or others, the situation should be considered a medical emergency. The best place to seek treatment for this level of anxiety is in an hospital emergency room or psychiatric facility that offers emergency intake.

What types of professionals treat anxiety disorders?

There are many professionals that are trained to treat people suffering from anxiety disorders. Some are more specialized than others, and have more specific training for specific subsets of the condition like phobias or OCD. Unfortunately, the quality and quantity of practitioners can also very greatly from one location to another. Scarce treatment options in a local area or very specific needs are both great reasons to consider eTherapy, where you meet with a practitioner via a face-chat application over the internet. The key is to find what works best for you in your unique situation.

“Scarce treatment options in a local area or

very specific needs are both great reasons

to consider eTherapy”

If researching providers seems overwhelming, a good way to start is with a family doctor or school counselor if the situation involves a child or teenager. Because these individuals are already known, trusted, and familiar with the situation, they may be first to spot red flags or other significant changes. While these providers are trained to recognize the basic symptoms of mental health disorders, their greatest strength is probably evaluating your current state against baseline and referring you to a colleague who can provide more specialized treatment.

Furthermore, a family doctor is able to run blood tests, and complete a physical exam to rule out any additional medical conditions (such as a thyroid disorder) that may be contributing to your mental well-being.

If it’s time to seek specialized treatment, all potential patients should educate themselves about the types of providers available, as it can get confusing. To begin with, anxiety disorders should ideally be diagnosed and treated by a licensed professional only, not a self-proclaimed healer or religious leader. When researching licensed provider types, these are are the most common:

A psychiatrist is medical doctor who is able to prescribe medication and specializes in mental health. They are able to do blood tests and a physical exam and offer treatment as it relates to your mental health. They can be more expensive than other types of mental health professionals and may not offer other forms of treatment that you may wish to try.

A physician assistant (PA) is a comparatively newer addition to the types of mental health practitioners available. They are often more affordable and easier to access than a psychiatrist, and can prescribe medication. There are now PA residencies that prepare the practitioner specifically for psychiatric work, meaning that a PA may have received fairly extensive training. Because the field is still evolving, it’s best to check their website or ask the PA’s office what educational background they’ve received.

strong>Psychologists have master’s degrees, are board-certified in their state, and may specialize in a particular area like family therapy, PTSD, etc. Psychologists are trained to use a variety of therapeutic techniques, including pioneering practices like EMDR. Psychologists are not medical doctors; they do not prescribe medication but can refer you to someone who does if they judge it to be merited. Compared to other providers (besides psychiatrists), they are more covered by insurance companies.

Licensed therapists (LPC) and social workers (LCSW) are also trained mental health professionals, and their level of training can vary from master’s to bachelor’s levels of education. To practice therapy, however, they must also have undergone licensing exams. On the spectrum of diversity and affordability, these clinicians are usually the most affordable and culturally diverse. While they may have less training than other practitioners, the scope of their work often makes them more connected to other community resources.

Some factors to consider when selecting a mental health professional are:

- Cost: Different professionals charge different rates. The cost can vary by the education and experience of the professional, and by the type of treatment. For example, group therapy is usually less expensive than individual therapy sessions. The cost of the professional’s time is shared all the group members rather than by just the individual. Online counseling is becoming more and more popular and it is typically much less expensive than in office counseling.

- Convenience: It is important to select a course of treatment that works with your lifestyle. Your success is dependent upon your ability to stay committed to your treatment plan, and show up for your appointments. If your life is very busy, or you live somewhere remote, one option to consider is online therapy. With online therapy you are able to connect with your counselor from your computer or mobile device, rather than having to go into a physical office for your scheduled sessions.

- Comfort: Talking about your emotions and mental health is very personal. If you are not comfortable with your counselor, you will not be as open, and your progress will be limited. It is important to find the right fit for your individual needs. There is more to a great mental health professional that just their credentials, or success rate. Talk to them, ask questions, and make sure they are a good match for you personally. Do you want to speak with someone of your own gender? Does their age, or religious background make a difference to you? What matters is connecting with the right professional that will help you overcome your challenges and find your path to happiness.

What Types of Treatment are Available?

There are a number of effective methods for treating anxiety disorders. Professional counseling, medication, peer support, and other coping skills like exercise can all play an important role in helping people manage their symptoms. Some people may find success utilizing just one method, but most find a combination of techniques work best.

The most common form of treating anxiety disorders is with psychological counseling. This may include psychotherapy, CBT or DBT, exposure therapy, or a combination of techniques. This therapy may occur in a group therapy setting or in individual sessions with the client and the counselor.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a popular and effective treatment method for anxiety disorders. This method aims to recognize and then change the thinking patterns associated with the anxiety and associated feelings, decrease the occurrence of negative feedback loops, and change the way individuals react to their individual anxiety triggering events. CBT is used for specific subsets of anxiety, too, including phobia and PTSD.

Group therapy and support groups are another form of treatment for anxiety disorders. Meeting with other people who share your challenges can be helpful and supportive. Knowing you are not alone in these situations can provide strength to overcome and endure. These groups are often led by a mental health professional and are made up of others with a similar diagnosis. A group setting helps individuals stay accountable for reaching their goals and offers beneficial social support.

Online counseling or online therapy is a new form of therapy that has been gaining in popularity recently. There are several web based companies designed to connect clients with counselors via the internet. The counseling sessions are accomplished through messages, video calls or voice calls between therapist and the client. These services are routinely more affordable than traditional, in-office sessions, and are far more convenient. The flexibility to

message your counselor at any time or any place is helpful for those that have a very busy schedule, have transportation difficulties or live in remote areas. It also allows for more frequent interaction between the client and their counselor. They can communicate in the moment when life becomes challenging, rather than waiting for a pre-scheduled appointment.

Medications are often also commonly used to treat anxiety disorders. These vary in effectiveness and need to be prescribed by a medical doctor, such as a psychiatrist. Some of these drugs include antidepressants, benzodiazepines, tricyclics, and beta-blockers. Unfortunately, anti-anxiety drugs like benzodiazepines can cause drowsiness and are highly addictive; doctors are moving away from prescribing them to people suffering chronic anxiety issues. All drugs have some side effects which should be considered.

Outside of the professional setting, there are other things that individuals can do on their own to help manage anxiety. These techniques are often taught by mental health professionals to their clients to use as a tool throughout their life whenever they experience moments of anxiety. These coping skills may include cognitive therapy techniques like reframing, avoiding black-and-white thinking, or mapping an emotional state. Having these tools readily available can give a person a sense of power over the anxiety disorder and allow them the ability to proceed with the challenges of daily life in spite of their history with an anxiety disorder.

“Learning to slow and control your breathing

is an excellent way to shift your focus and

initiate relaxation.”

Learning different methods to cope with intense emotions where cognitive reasoning may no longer be possible is also helpful in managing anxiety symptoms. These tools include relaxation techniques such as practicing mindfulness, guided imagery and breathing techniques. Learning to slow and control your breathing is an excellent way to shift your focus and initiate relaxation.

Guided imagery is a technique that involves using your imagination, or an outside prompt like a recording, to transport your mind to a calm and relaxing environment, allowing your mind to relax and the anxiety to pass. Unlike mindfulness, guided imagery focuses specifically on removing oneself from the situation in a healthy way (as opposed to maladaptive coping skills like alcohol). The increasing popularity of smartphones means that there are now many guided imagery podcasts, apps, and other options available free over the internet.

Mindfulness is the practice of living in the present moment, originally drawn from meditation practices in Buddhism. While this may sound very “new age”, researchers have actually been studying the effect of mindfulness on the brain, and there seems to be concrete evidence pointing its role in helping a variety of mental illnesses; one study found that mindfulness reduced physical symptoms of emotional distress like heart rate and blood pressure. Focusing on the present moment can often pull a person who suffers from an anxiety disorder away from the memory, triggering emotion or event, and avoid a panic attack. Consciously choosing to focus on the safety and pleasantness of the present moment can effectively mitigate an anxiety attack.

“One study found that mindfulness

reduced physical symptoms of

emotional distress like heart rate

and blood pressure.”

Finally, there is emerging evidence that exercise can have a huge impact on anxiety. Running, in particular, has been associated with notable declines in anxiety scores in multiple studies. Fortunately, non-runners have options too. Simply walking for around half an hour, particularly in green or forested places and alongside mindfulness techniques, has a documented calming effect, as does yoga. Scientists think the positive effect exercise has on anxiety is due to several factors, including feel-good endorphins released by the brain during physical activity, physical movement facilitating a present/mindful mental state, and even the physical release of stress or tension.

“The bottom line is that those suffering from

anxiety do not need to feel hopeless or

helpless”

Living with an untreated anxiety disorder is difficult to say the least. Normal, everyday tasks can become insurmountable. In an attempt to avoid triggers, an individual can become isolated, making employment difficult, and causing relationships to break down. Without treatment, anxiety disorders tend to worsen over time, and as the suffering increases, the ability to manage daily life decreases. To make matters worse, untreated anxiety often invites self-medication in the form of substance abuse or other maladaptive coping behaviors, which ultimately makes the problem much more complicated to treat.

If you suspect that you, or a loved one, are suffering from an anxiety disorder, please seek professional help without delay. If it’s a true emergency involving a person being a danger to themselves or others, an emergency room is the best choice. Otherwise, there are many proven successful treatment avenues to explore with a wide variety of mental health professionals available to assist with whichever particular challenges you’re facing. It’s also important for everyone to tackle the stigma around anxiety and mental illness by encouraging open and honest discussion and advocacy, as well as not misusing terms like OCD or PTSD. Anxiety sufferers should also remember that they are not alone; anxiety is the most common mental health diagnosis both in the US and worldwide.

Finally, and most importantly, anxiety disorders can become manageable instead of debilitating with professional treatment. With the unprecedented number of practitioners as well as treatment techniques available today, there are options for a huge variety of personal situations, backgrounds, and budgets. The bottom line is that those suffering from anxiety do not need to feel hopeless or helpless. If you’re ready for help, reach out today.

Talk to an Expert about Anxiety Today!

We offer a 3-day free trial to see if online counseling is a good fit for you.

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/info/anxiety

- http://www.apa.org/

- https://www.healthyplace.com/anxiety-panic/articles/history-of-anxiety-disorders

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/heart/themes/shellshock.html

- https://adaa.org/

- https://adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics

- https://adaa.org/living-with-anxiety/children#

- https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/04/19/adrenaline-cortisol-stress-hormones_n_3112800.html

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anxiety/symptoms-causes/syc-20350961

- https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

- https://books.google.com/books?id=1BfYBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA402#v=onepage&q&f=false

- http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/02/stressed-nation.aspx

- https://books.google.com/books?id=1BfYBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA402#v=onepage&q&f=false

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3684250/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5007197/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000579671200157X

- https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/related-illnesses/other-related-conditions/stress/physical-activity-reduces-st

- https://www.healthline.com/health/anxiety-diagnosis

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/info/anxiety/anxiety-treatments.php

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/urbansurvival/201712/new-study-finds-meditation-walking-reduces-anxiety

- https://adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics